|

|||

Ken Colyer's Jazzmen: New Orleans to London (1953)

This is one of the most exciting records ever issued by a British jazz band. Added to the lively quality of the recording, is a performance that is full of enthusiasm, ideas and rhythm. New Orleans has really been brought to London at last for Ken Colyer, drawing on personal experience, has recaptured the spirit of New Orleans jazz and got nearer to a genuine performance than any British band has ever done before. The first noticeable thing is the absence of the piano, an instrument which was never used in the very early bands. The clarity achieved by this arrangement more than makes up for the absence of a popular instrument which, unfortunately, usually has a clogging effect. The emphasis is on ensemble work – as it should be. They achieve a degree of relaxation and of easy rhythm that is rare in a white band, British or American. The solos are unobtrusive because they fit so well into the general spirit of the music, and the total effect is that of one of the best co-ordinated groups that has yet been recorded. One of their best effects is heard in the very fine use of derby and cup mutes by the trumpet and trombone when backing up the clarinet solos. Ken Colyer on trumpet plays an authoritative lead with very able backing from Chris Barber whose trombone playing is of the very best tailgate variety, and Monty Sunshine whose clarinet playing is a triumph of clarity and appropriate ideas. This is a front line of experienced players all of whom have led their own bands, and whose mutual understanding is a miraculous thing only very rarely achieved in jazz. Tony Donegan on the banjo, was another bandleader, and his group also included Jim Bray, the bass player with the Ken Colyer Band. Ron Bowden on the drums, who used to play with the Monty Sunshine quintet, completes a rhythm section which gives the front line all the support and encouragement that they could possibly demand. Ken Colyer must feel very gratified to have achieved this wonderful result for his life has been wholeheartedly devoted to New Orleans jazz. He started playing the trumpet ten years ago, learning entirely from gramophone records. He joined the Merchant Navy soon after this, which gave him an opportunity to meet many famous American jazzmen during his travels. He left the service in 1948 and formed his first band with his brother, Bill Colyer, a band which had a considerable success on radio and television. Also in the group were Monty Sunshine and Ron Bowden. In late 1951, Ken Colyer rejoined the Merchant Navy with the intention of reaching New Orleans so that he could study jazz at first hand. He travelled around for twelve months, visiting New Zealand, Africa and Australia before he finally got there. He spent four months in New Orleans meeting and playing with some of the living creators of real jazz – George Lewis, Emil Barnes, Johnny St. Cyr, Paul Barbarin, Ray Burke, Sharkey Bonano, Lizzie Miles and many others. He returned to England in March 1953 and, fresh from these fruitful contacts, joined and led a group already formed by Monty Sunshine and Chris Barber. This became Ken Colyer's Jazzmen, and after a tour of Denmark and Sweden, they took up residence at a famous London jazz club, to become one of the country's best traditional jazz groups. Their repertoire includes original rags, blues and spirituals, and at least one face-lift applied to a popular song – in this case, Isle of Capri. Goin' Home and La Harpe Street are original compositions by Ken Colyer and it is this last tune, together with Harlem Rag which provides one of the most integrated moments on a record which is full of good things. We can be certain that this is the genuine spirit of New Orleans jazz; but even more important is the fact that it sounds new, for this group has a style all of its own which is original and alive. It is this re-interpretation of the tradition which serves to keep jazz a vital and intriguing music. |

|||

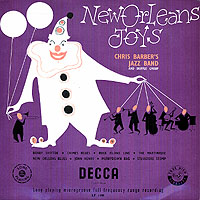

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: New Orleans Joys (1954)

This is New Orleans jazz – a tradition of music rather than a form, and as distinctive a tradition as English folk-music or Spanish sardanas. And like all traditions there can be no tampering with it; it is as big a failure to be deliberately archaic and merely copy what has gone before as it is to try to force new ideas on to an already perfect idiom. The only way to handle New Orleans jazz is to have an innate feeling for it and then to do your best, striving only for tightness of phrasing and rhythm. Because this can be heard on record almost as well as in actuality, it has been possible for British and European players who love the music sufficiently to produce a music full of the spirit of traditional jazz and, in some cases, of a standard to be considered amongst the best. This record is an example. Here is a group of young players who can match their enthusiasm with instrumental skill and an almost uncanny knack of playing together, producing one of the most integrated sounds that has been heard on a jazz record. A previous record by almost the same group proved to be one of the most exciting jazz issues of the year in this country and this present record keeps up to those standards and adds something extra in the way of a couple of skiffle numbers. Chris Barber was intended to be a mathematician and studied for this until a sudden enthusiasm for jazz quickly put all such ideas out of mind. He studied the violin first of all from the age of twelve but turned to his present instrument, the trombone, in 1948. He formed his first band in 1949 and a second which had considerable success playing music in the two cornet Oliver style in January 1950. This band kept together until January 1953, including amongst its players Dickie Hawdon on first cornet, now with the Don Rendell band. The next band he formed with Monty Sunshine and shortly afterwards Ken Colyer was asked to join to lead it on trumpet The result is to be heard on the magnificent "New Orleans to London" long playing record (Decca LF1152), recorded on November 4,1953. In June 1954, Ken Colyer and the band parted company, Ken pursuing his own ideas with another group which can be heard on "Back to the Delta – a New Orleans Encore" (Decca LF1196), and the rest of the band with the addition of Pat Halcox on cornet, sometime leader of a West London amateur band, made this record after six weeks playing together on July 13 1954. It was only just made as Chris was only two days out of hospital after two weeks with glandular fever. As well as Pat Halcox (cornet), Chris Barber (trombone), and Monty Sunshine (clarinet), the rest of the band is still the same – Lonnie Donegan (banjo), Ron Bowden (drums), Jim Bray (bass) and the band continues the same policy of dispensing with the piano, which gives the group a greater clarity to balance the loss of a very important voice in the line-up. The skiffle group which plays two very fine numbers on the session is composed of Lonnie Donegan (guitar and vocal), Chris Barber (bass) and Beryl Bryden (washboard), and Rock Island Line is surely one of the finest skiffle numbers ever recorded in this country. This newly awakened interest in the true Negro "race' music which Chris and Lonnie have been fostering for some years, opens up a whole new field of traditional jazz adding to the already vast repertoire of classic numbers. It is a music which a little skill and enthusiasm can produce with quite good results; in the hands of our present experts it becomes exciting beyond all expectations in consideration of its simplicity. John Henry is the tale of a legendary folklore hero who built railway tunnels and killed himself with a new steam-driven tunnel digger. Rock Island Line is the story of some shady business on a railroad which "goes down into New Orleans". The band numbers include Bobby Shaftoe, a convincing proof that any material such as this old English folk tune can be turned into an exciting jazz number, Chimes Blues – a King Oliver number which Jelly Roll Morton used as Mournful Serenade, in which Chris Barber's arrangement makes a very effective use of the brass in place of the usual piano chimes. Merrydown Rag is a Chris Barber original written in the classic ragtime tradition with an AABBACCDCC thematic treatment. Stevedore Stomp is an early Ellington number transcribed for New Orleans band, while New Orleans Blues is a Jelly Roll Morton piano number similarly arranged. The Martinique is a Wilbur de Paris number which he has recorded with his Rampart Street Ramblers (Felsted EDL87010) so there is a very interesting comparison of the two treatments of this 'Spanish tinge' style number. This is a fine feast of jazz proving conclusively that the New Orleans tradition is by no means dead in England, and promises well for our future enjoyment. |

|||

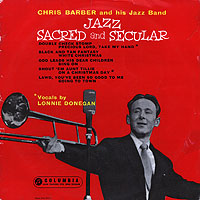

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Jazz Sacred And Secular (1954 & 1955)

Notes by Brian Rust The story of Chris Barber's rise to pre-eminence among British jazz musicians is one of a mixture of sheer hard work and a sincere love of jazz music. While still at school, young Chris, who was born on April 17th, 1930, was bitten by the jazz virus, and after going through the usual stages of being fascinated by the current vogue for big-band swing, his taste matured early and he settled for what is now rather loosely described as "traditional" jazz. In his case, however, this did not mean a slavish imitation of semi-legendary New Orleans pioneers, however sincere a form of flattery that might be. Instead, having learned the basic facts of violin playing, Chris Barber applied himself to mastering the trombone, in between studying for his final examinations at school and collecting rare jazz records. (If I may indulge in a personal reminiscence for a moment, I can recall many a pleasant Sunday morning in 1947 and 1948 when Chris and I would play jazz records and discuss their merits and demerits, their origins and personnels, and it was from him that I obtained my first set of Kid Ory records, not to mention other much rarer items.) Having a phenomenal memory for figures and the ability to work out complicated mathematical problems with the minimum of paper work, it was originally intended that Chris Barber should be an actuary. But his love of jazz led him to form his own band after sitting in with various semi-professional groups in London, at first rather shyly, later with the calm confidence that is his today. When Ken Colyer, another of Britain's leading jazzmen, returned in the spring of 1953 from New Orleans, where he had studied and played with the greatest living musicians in the original idiom, he formed a band that included Chris Barber on trombone, Monty Sunshine on clarinet, Lonnie Donegan on banjo and guitar, Jim Bray on bass and Ron Bowden on drums. With this group, young Barber made many very successful appearances in public and on record, but neither he nor the other four men were entirely in sympathy with Colyer's "purist" ideas, and in the summer of 1954, they parted from him, and with Pat Halcox on cornet, formed Chris Barber's Jazz Band, which is how they appear on the record in this sleeve. The ten tracks here presented demonstrate fully the quite unusual versatility of this band. Whereas most bands of this kind – with or without a piano – concentrate on "standard" jazz numbers that have been worked to death over and over again, Chris Barber sees to it that his men are capable of interpreting anything and everything suitable for adaptation to the requirements of his music. So it is that we find Irving Berlin's superlatively nostalgic White Christmas being made perfectly recognizable as a medium-tempo stomp, along with old English folk songs linked to the blues (On a Christmas Day), Negro spirituals with vocals by Lonnie Donegan (Precious Lord) and without vocals at all (Sing On), and something which Barber pioneered: the playing of Duke Ellington's often elaborate music by a six-piece band, perfectly balanced, and achieving a freshness and virility that characterized the original Ellington masterpieces back in the Cotton Club days of 1927-1931. Pat Halcox in no wise copies the late Bubber Miley's (or Cootie Williams') growl-muted horn. He simply gives his impression of their work through the medium of his own. Certain other "johnny-come-lately" bands have essayed this procedure with quite disastrous results. Chris Barber's band sounds perfectly at ease, as much with Ellington as with Berlin, or with any and every other composer. Success is theirs, but success has brought its harvest of inevitable criticism, some well-meant, some obviously carping. It is sometimes said that the band has too much polish, that its music prances, or that it lacks drive. Analysed, these criticisms usually mean that the band plays crisply and in tune, that it has a firm, if light and easy beat, and that instead of generating a pulse like a steam-hammer (and with as much subtlety), it soars along fluidly. In these days of deliberately (or perhaps carelessly) playing out-of-tune like . . . well, we will name no names, the polish, neatness and attention to detail is no bad thing. "It is wonderful being able to play jazz and make a good living at it," says Chris Barber. Long may he continue to do so! |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber Plays (1955)

Notes by Brian Rust Chris Barber was born on 17th April, 1930, and formed his first jazz band in 1949, having studied the violin, and subsequently trombone at the Guildhall School of Music. He also plays string bass. His present band was formed in 1954, and the unit, which includes in its repertoire spirituals, blues, marches, popular songs and Duke Ellington standards, has rapidly become one of the best-known British jazz bands. The eight numbers presented on this record are all composed by, or associated with, the two unrelated Williams' from New Orleans – Clarence and Spencer. Spencer, the elder, was born in 1888 and Clarence ten years later. Both have written many successful popular songs, but it is as jazz composers that they are best known. Spencer lived for many years in England, in Paris, and when last heard of had settled down in Sweden. Clarence, on the other hand, has never left America; at present he owns an antique shop in Harlem. Spencer has made comparatively few records, while those for which Clarence was responsible run into many hundreds. You Don't Understand is a collaboration between the two Williams' and James P. Johnson, one of the doyens of the Harlem school of jazz piano. The number was written in 1929, and is in the form of a conventional thirty-two bar popular song. Tishomingo Blues, named after a Southern township, was first recorded in 1928 by Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra. The melody is in the blues idiom, though it does not follow the traditional twelve-bar form. In Wild Cat Blues we have an example of Sidney Bechet's work as a composer. He recorded this number as a member of Clarence Williams' Blue Five in 1923. Ugly Child was written as a parody by George Brunis, pioneer white New Orleans trombonist, on a song composed by Clarence Williams in 1916 – Pretty Doll. Ottilie Patterson sings the parody with tongue-in-cheek humour. Everybody Loves My Baby has been a standard vehicle for jazz bands and commercial groups alike since it was written in 1924 and first recorded by Clarence Williams' Blue Five, with Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet. Careless Love has its origin in Southern folk music and was first notated by Spencer Williams, who remembered hearing it as early as 1896 in Birmingham, Alabama, sung by a white washerwoman hanging clothing on a line. Careless Love is also known by the title Loveless Love which W. C. Handy bestowed upon it when in 1921 he published the song, adding a verse and fresh lyrics. Clarence Todd was a coloured cabaret artist who often recorded with Clarence Williams during the mid-'twenties, sometimes under the name of Singin' Sam. Between them, they wrote Papa De-Da-Da and Eva Taylor, Mrs. Clarence Williams in private life, recorded it with lyrics about a handsome ladies' man from New Orleans. The Barber Band offer it in non-vocal form, but pay homage to its composer by concluding with the syncopated three-note phrase with which Clarence Williams' own version ends. Lastly, High Society, which illustrates the Barber Band's flair for stirring marches. Porter Steele, a white musician, originally composed it in 1901, and it has since been played on record by almost every kind of combination. It has also been credited to such divers composers as Louis Armstrong, Armand Piron, Jelly Roll Morton and Clarence Williams, all of whom have written arrangements on the original march theme. It follows the pattern of John Philip Sousa's marches of the turn of the century, with a beautiful trio theme which has become a test piece for clarinetists. |

|||

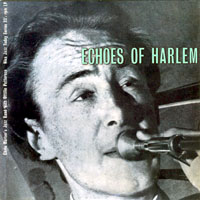

Chris Barber's Jazz Band with Ottilie Patterson: Echoes Of Harlem (1955)

Notes by Brian Rust Pursuing their policy of presenting to the discerning jazz enthusiasts old and new numbers played freshly and originally within the normal concept of the term "traditional jazz", Chris Barber's Jazz Band here offer eleven songs associated with Harlem in the 'twenties and early 'thirties. Firstly, Doin' The Crazy Walk is a very little-known early composition by Duke Ellington. So far as can be traced, this is the first recording of the number ever made, for even the Duke himself never committed it to wax. It comes from the same period as such lively stomps as Stevedore, Double Check and Shout 'Em Aunt Tilly, and has a good-time rent-party sound about it. Next, the better-known hit tune from the show "Blackbirds of 1928", with music by Jimmy McHugh and lyrics (not sung here) by Dorothy Fields, Baby. This has been recorded by, amongst others, Adelaide Hall, Ethel Waters and Lillie Delk Christian, the latter being accompanied by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Four. Pat Halcox is the featured soloist in this version, a special characteristic being the beautiful shading of his playing from pianissimo to mezzo-forte. Following the almost wistful sound of Baby, we have another lively number by the same team of composers – Magnolia's Wedding Day. This is the first recording ever made in England, so far as is known. Although a show tune of the period, it has not staled with the years, a sure test of a good song. Dixie Cinderella, which is a showcase for Monty Sunshine's inventive clarinet playing, is a hitherto unrecorded early number by the team that gave us Black and Blue, Ain't Misbehavin' and other tunes from the Harlem revue "Connie's Hot Chocolates" – Thomas "Fats" Waller, Harry Brooks and Andy Razaf. Chris Barber plays bass on this, and has a solo to demonstrate his skill. Notice his adherence to the melody line, which as usual with this group of composers, is strong and appealing. Side One concludes with the first appearance on this disc of Ottilie Patterson, the brilliant blues singer from Northern Ireland. The New St. Louis Blues contains some somewhat little-known lyrics, to which Pat Halcox provides a moving obligato, and Monty Sunshine seems – without copying at all – to have Larry Shields in mind, for that pioneer white New Orleans clarinettist cast his 1921 recorded solo on this number in a similar mould. Another vigorous Fields-McHugh collaboration opens Side Two. This is Here Comes My Blackbird, again hitherto unrecorded. Many of these Blackbird songs were written for the late Florence Mills, whose tragically early death at thirty-two in 1927 robbed the stage of one of its most attractive personalities. Can't We Get Together is another Waller-Razaf production, though neither of them ever recorded it. Lonnie Donegan drops out for this version, the first in England, and everyone in the front line has something to say. There have, of course, been literally dozens of records of I Can't Give You Anything But Love since its first appearance in 1928, along with Baby, in Lew Leslie's "Blackbirds of 1928". Among these was one by Adelaide Hall, accompanied by "Fats" Waller at the organ; there have been others by singers and players of every colour and nationality, from Duke Ellington and his Orchestra to Seger Ellis, of the high tenor voice, supported by Tommy Dorsey, Eddie Lang and others. This present version is a model of restraint. Ottilie Patterson reappears for a chorus and a half, singing with something of the style of Adelaide Hall, its creator. One of the most interesting features of Sweet Savannah Sue, which follows, is the neat lead-in to his solo by Chris Barber. A single note repeated several times presages a finely-constructed half-chorus. This number, composed by "Fats" Waller in 1929, and recorded by him as a piano solo, as well as by Louis Armstrong, and other, lesser men, is seldom heard today. Even "Fats" himself had forgotten it when Hugues Panassie requested him to play it one night in Waller's apartment. Porgy, dated 1930, is yet another Fields-McHugh melody, played here as a solo for trombone by Chris Barber. Ethel Waters sang this delightful number when it was first published, and the leader's horn here echoes the lyric quality of Miss Water's voice. The selection concludes with Diga Diga Doo, the third number from "Blackbirds of 1928" (by Fields and McHugh, of course!) a tune which was originally part of Duke Ellington's repertoire of that period. It is customary in some circles nowadays to shake an admonishing finger, as it were, at the manners and modes of the late 'twenties; but as this set shows, it was a period exceptionally rich in good tunes that time has dealt with lightly. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber Plays, Volume 2 (1956)

Notes by Brian Rust With Chris Barber's Jazz Band firmly installed as a popular fixture in the British traditional jazz field, comment about its history becomes superfluous, so let us consider the music presented on this disc. Our opening number, Whistlin' Rufus, is one of the oldest tunes in the Barber repertoire. It was written in 1897 by Kerry Mills, a white composer of popular marches and cakewalks such as At A Georgia Camp Meeting and Red Wing. It had a great vogue in late Victorian and Edwardian England, long before the arrival here of Tin-Pan Alley's conception of ragtime. The great banjoist Oily Oakley recorded it in London in 1903 to the piano accompaniment of Landon Ronald, but by its nature it lends itself to treatment in the jazz idiom, with comparatively little solo work, relying more on ensemble passages to give the period flavour of an old-time dance band. Big House Blues is one of the lesser known numbers associated with Duke Ellington, whose band recorded it in 1930 under the pseudonym of "The Harlem Footwarmers". It is a slow, moody, rather eerie piece in the idiom of The Mooche; Pat Halcox plays a growling muted cornet solo following the lead given by such masters of the style as Bubber Miley and Cootie Williams, and Monty Sunshine sounds very much like Barney Bigard, who was Ellington's clarinettist on the Duke's record. The tune April Showers is usually associated with the late Al Jolson, who first introduced it in his show "Bombo" in New York in the autumn of 1921. It became a hit at once, and has passed into the category of standard popular numbers following several recordings by Jolson himself and by numerous dance bands such as Paul Whiteman's. It is very rarely heard as a jazz vehicle, however, and each member of the front line has a long solo in which to work improvisations that are really fresh. One Sweet Letter From You was composed in 1927 as another popular tune, this time by Harry Warren, hero of hundreds of melodious and catchy numbers from Pasadena in 1924 to September In The Rain in 1937, and many more before and since. Kate Smith and Sophie Tucker each recorded it, each accompanied by a Red Nichols group, and there were again hosts of good, bad and indifferent straight dance versions at the time when it was a "plug" number. In 1945, the great New Orleans cornettist Willie "Bunk" Johnson made another recording, without lyrics, and since then it has been adopted as a standard jazz piece by traditional bands the world over. Monty Sunshine is the soloist in his own charming Hush-a-Bye in which, accompanied only by banjo and string bass, he plays effortless variations on a most attractive melody. Though tender and sweet, it never cloys; it has sentiment, but no sentimentality. Lastly, We Shall Walk Through The Valley is a traditional spiritual sung by Dick Bishop, one of the members of Lonnie Donegan's Skiffle Group. It begins slowly and in a sweetly sad strain, but after a few bars the band strikes up with a rousing march, which suggests that the number was originally one of the "funeral parlour" repertoire like Oh, Didn't He Ramble! Its simplicity and directness are worth a hundred wordy sermons. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber Plays, Volume 3 (1956)

Notes by Brian Rust Here is the fourth album of numbers from the Chris Barber book. Since the departure of Lonnie Donegan, the original banjo and guitar player, Dick Bishop has taken his place, and Dick Smith now plays bass instead of Mickey Ashman. Otherwise, the ingredients are as before. Thriller Rag is an early number, sometimes credited to one May Auferheide. It has a beautiful archaic melody of which the band makes the most. There are scores of ragtime numbers like this, dating back beyond the turn of the century, which seldom receive attention; it is thus particularly to the credit of the Barber band that they include such material in their repertoire. Texas Moaner is a 1924 composition by a rather obscure New York blues artiste named Fae Barnes, who recorded for Paramount during that year. She did not record this number, so far as is known. Laura Smith did, however; also Eve Taylor – the latter in the august company of Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet. It is an attractive blues theme. Sweet Georgia Brown, a Tin Pan Alley creation of 1925, has always been a favourite jazz standby. Ben Bernie gets credit for having written it, and he recorded it with his Hotel Roosevelt Orchestra at that time, with Jack Pettis, late of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, in the reed section. On this recording Chris Barber is featured solo, with much of the shouting timbre of a J. C. Higginbotham in his phrases. Mention of Jack Pettis brings us to Bugle Call Rag, which Pettis recorded with the original Friars Society Orchestra in August, 1922. (He later made another version, in May, 1929; both were labelled Bugle Call Blues.) Since those early days, it has been the victim of every commercial bandleader's whim, notably Harry Roy's, and has also been attempted by other entertainers from cinema organists to mouth-organists. It is good to hear it well-recorded by an intelligent jazz unit. Note especially the three voices of the front line in the coda. Sidney Bechet, composer of a hundred attractive melodies, has, in Petite Fleur, a true Creole tune, one of his happiest inspirations. Monty Sunshine acknowledges the composer gracefully, and there is a neat bridge passage for Dick Bishop's guitar, sounding rather like a zither and lending a wistful air to the performance. The last number dates back to 1921. Wabash Blues, quite a creditable commercial blues, is another long-established favourite in the jazz repertoire. It was used as a theme tune for a New York production of the period, "Rain", and has been recorded by a gamut of bands, from the Benson Orchestra of Chicago to the Charleston Chasers. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band with Ottilie Patterson, Johnny Duncan and the Skiffle Group: Chris Barber In Concert (1956)

A blisteringly hot day in early summer; the trees in the Thames-side meadows shimmer in the haze; couples lolling on the warm grass by the towpath seem transfixed by the heat – or is it by the sight and sound of the steamer cruising upriver from Richmond, with two jazz bands beating it out on the scorched planks of the fo'cstle deck, half a hundred dedicated fans jiving on the poop and two hundred more dancing frenziedly amidships? It is 1949. The London Jazz Club is indulging in Britain's first-ever "riverboat shuffle". And in the steamer's cockpit a freckled, straw-haired boy nervously raises a trombone to his lips, preparing to blow his first-ever note in public. Jazz on the river seems as daring and romantic to him as it does to the towpath couples under the beating sun; none of them realise that, in seven short years, jazz music will have come to be so universally accepted in Britain that it will occasion no comment if the biggest draw of all in the concert world should be – a jazz band. Certainly the freckle-faced boy, an actuary-in-training at an insurance company, has no idea that he will be the leader of such a band. Even though his name is Chris Barber. And yet, when this LP was recorded, at a Royal Festival Hall concert in December, 1956, Barber actually was leader of the biggest musical draw in the country – a band so successful that, in the course of its nation-wide one-night stands, its Sunday concerts, its radio and TV and jazz club appearances, it had displaced the famous swing bands, the palais orchestras, the Latin-American groups, the traditional jazz units and all other opposition in the fight to win the public's esteem! The links between Chris Barber, the diffident son of a statistician and a headmistress, who first played in public on the river in 1949, and Chris Barber the successful bandleader, a household name and owner of three expensive sports cars in 1957, were forged in the fire of enthusiasm kindled that sunny afternoon when Chris found himself blowing in the company of such famous jazzmen as Humphrey Lyttelton, Wally Fawkes and the members of the Dutch Swing College, all of whom were guesting on the riverboat shuffle. It was very shortly after this, to quote Chris himself, that "my interest in jazz got the better of my mathematical concentration – and the insurance firm and I decided to part company..." With Ken Colyer and Lonnie Donegan (both of them Show Business notabilities, too, today) he formed a band with the traditional two-trumpet lead employed by the late and great Joe "King" Oliver in the days of the beginnings of jazz. With this group, unashamedly based as it was on the New Orleans style of the early twenties, Barber went into intensive rehearsal in the winter of 1949, making his first public appearance as a leader in a jazz band contest run by the National Federation of Jazz Organisations at London's Empress Hall in the Spring of 1950. Six months later, he opened his own jazz club, named – and it is self-evident that he was still on a violently pro-Oliver kick! – the Lincoln Gardens Jazz Club… Thus, for three years, he progressed – until, in March, 1953, broadened somewhat in taste, he broke the band up, immediately forming another, distinctive in that it used no piano, with the help of the clarinettist, Monty Sunshine, and trumpeter Pat Halcox. A co-operative venture like the former group, this band differed in that it hoped to turn fully professional and make a living out of jazz. Surprisingly, it made the grade – but in so doing, lost the name of Barber as leader, Pat Halcox standing down in favour of Ken Colyer and the latter taking over the leadership by virtue of his drawing power as a man who had actually been to New Orleans and played there! For a year, the band prospered under Colyer's lead, and then he and Halcox switched a second time – the leadership again reverting to Barber. Since then it has remained practically unchanged – with one very important exception. An exception named Ottilie Patterson. Since the band first heard the astonishing singing of this ex-art teacher from Ulster in August, 1954, when she was holidaying in England, since they first implored her to join them on the same night, Ottilie has won for herself a permanent and unshakable niche in the affections of the British jazz and Variety public by the authenticity and emotional impact of her fabulous blues singing. Together with the Barber band, today she enjoys a successful routine as one of the country's top attractions of all time – a routine embodying two dates at London clubs, one day off, and four out-of-town dates each week. This LP, marking the third Anniversary of the present Chris Barber Jazz Band, brings you, the listener, a typical example of one of these dates: with the exception of a couple of skiffle pieces, here is a whole concert captured on disc – a living example of just what good British jazz can be, and why the Barber brand of it, in particular, is so intensely successful all round the country… |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber Plays, Volume 4 (1957)

Notes by Brian Rust Here is another representative cross-section of the Chris Barber Band output. As you will see, there are two selections by Monty Sunshine alone with the rhythm, and two featuring Ottilie Patterson. Out of the total of seven titles, three are sacred music, yet even the sternest theologian could hardly take exception to the tender simplicity of Old Rugged Cross, that favourite nineteenth-century hymn, played as Monty Sunshine does here. With only the slightest variation on the melody he transports it from being just another song of praise to being a reverent musical experience. When the Saints Go Marching In is far too often heard pounded out at a viciously monotonous tempo, but here, complete with lyrics that give meaning to the performance, we have as fine a version of this enormously popular jazz favourite as has ever been heard. No-one knows exactly when it originated; the Kentucky hill-billy singers Frank and James McCravy have laid claim to this, but the truth will probably never be known. Just A Closer Walk With Thee is a true Negro spiritual, brought to our notice first by George Lewis, the veteran New Orleans clarinettist. Here again, we have a relaxed, slow tempo with lyrics sung as sincerely as anyone could wish, with a doubling-up of tempo to finish with. Of the secular numbers, the Barber band produces a composition of originality and charm in Pound of Blues. Slightly Ellingtonian, with the merest suggestion of modernism, this is one of the few examples of how jazz can sound fresh and new within the so-called "traditional" framework. (It really is about time we stopped labelling our jazz music, or at least, that we applied the correct labels. Surely the truth is that music is either jazz or it's not, and if it's jazz, then it's either good or bad jazz. This is a good jazz, and it can safely be left at that. It sings, it swings, it has all the oft-quoted Morton ingredients and yet it does not sound as though it had been raked up from the remote corners of some museum.) The two colossi of what, if we are to keep labels, should be termed "mainstream" jazz, King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, were each responsible for one of these two numbers: Olga (introduced by Oliver in 1930) and Bye and Bye (introduced by Armstrong in 1939). Olga was originally recorded by Joe Oliver in May 1930, and has not been re-made by anyone since. It is offered here with a suggestion of the Duke, as well as the King; a fine relaxed piece of jazz, like Oliver's own. Then we have When You And I Were Young, Maggie. Originally a rather morbid drawing-room ballad of the type that enjoyed a great vogue during the 'seventies and 'eighties of last century, it must have been attempted by countless singers, singly and in duets, trios and quartets in the intervening years, until Mezz Mezzrow smartened it up and showed the world in 1938 what a potent bit of jazz it could be. Monty Sunshine's version is nothing like the original presentations, of course; he examines the theme from all angles, never runs out of ideas and never bores the listener. Which may be safely said of this entire presentation. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band with Ottilie Patterson: Chris Barber In Concert, Volume 2 (1958)

Notes by Les Page The scene is Birmingham, January 31st, 1958, and the enshrouding fog and bitter cold make a chilly welcome for the traveller on his way to the Town Hall. There, however, the enthusiasm of the waiting crowds help one forget the distasteful weather. The Chris Barber Jazz Band is again at the Town Hall, where we witnessed the first public jazz concert in this country a decade ago. Since then the capital of the Midlands jazz scene has welcomed Sidney Bechet, Eddie Condon, George Lewis, Big T, the M.J.Q. and Sister Rosetta Tharpe – the latter alongside the Barber Band, as well as British groups of national and local repute. And the audience has always been enthusiastic; occasionally demonstrably so! Nearly a year ago I wrote in "Jazz Music" that the jazz band of Chris Barber can sell out any provincial concert-hall, so great is the demand by audiences outside London. My words were no less true on this present occasion and again it was "House Full". It is the same for Barber's appearances in other Midland towns, whether in concert halls, Sunday theatre dates at Smethwick and Dudley, or at the University's Jazz Band Ball. Apart from the undoubted all-round technical ability of the Barber Band, I am convinced that much of their popularity is due to Chris's attention to details of presentation and to variety in programme planning. In other words, there is a balance between ensemble playing in the New Orleans tradition, and solo treatment of selected numbers which affords the opportunity to identify the characteristics of the individual musicians. From their signature tune, Bourbon Street Parade, the band get away to a fine start with Kid Ory's famous Savoy Blues – often played but not before recorded by Chris Barber's Jazz Band. And then Ottilie Patterson ... on this, her birthday to give us Moonshine Man and the beautiful Lonesome Road. Recently a German critic of repute called Ottilie "Europe's best female interpreter of the Blues", and we feel that after hearing her on this record the listener will agree. Each of the front-line trio is featured on this record. Monty Sunshine plays an old music-hall song of years gone by, Bill Bailey Won't You Please Come Home, which compares well with his better-known versions of tunes associated with Sidney Bechet and George Lewis. Monty's claim to be Britain's No. 1 trad clarinettist is firmly staked. Pat Halcox gives us You Took Advantage Of Me, a popular solo which must confound those who belittle his progress and prowess. Then Chris Barber plays Sweet Sue as a solo for trombone and rhythm with the audience clamouring for more. There have been numerous recordings of jazz concerts held in London halls. Indeed, Chris and his Jazz Band appear on Nixa with a Festival Hall recording made in December 1956 under the title "Chris Barber In Concert" (Nixa NJL 6), but this is the first time that jazz from a Provincial concert platform has been made available to the wide public on a major label, and it is fitting that it should be Chris Barber's fine swinging outfit, so popular with Provincial audiences, that bears the banner! |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber In Concert, Volume 3 (1958)

Notes by Derrick Stewart-Baxter The popular entertainer, the best-selling novelist and the latest hit from Tin Pan Alley usually have one thing in common … none of them are as good as the publicity agents would have us believe. Thus when one finds a jazz band whose records are in great demand and whose concert appearances, both in this country and abroad, are sell-outs, one becomes suspicious. The jazz fan who has not heard of Chris Barber's band (if such a person exists!) would be justified in asking: "Popular with the general public – where's the gimmick?" Furthermore, he would be unconvinced if he were assured that Chris has no gimmick, unless one counts a great enthusiasm for jazz and a sincere belief that good music well played can attract the public. The band base their music on the New Orleans pattern, around which traditional formula they have evolved a very personal style. Melodic and swinging, the group can be recognised the moment they commence playing. In a day and age when copyists are everywhere, Barber deserves full credit for originality. The front line possesses three most interesting soloists: Pat Halcox, trumpet, Monty Sunshine, clarinet, and Chris himself on trombone. This, coupled with a solid rhythm section, makes the Barber brand of jazz a very happy sound. This L.P. is a memorable one for all Brighton enthusiasts for it is the first time a jazz concert has been recorded on the historic and world-famous Pavilion Estate (of which the Dome forms a part) conceived by John Nash at the request of the Prince Regent (later George IV). The Dome concert hall, originally part of the Royal stables, seats 2,100 people, is acoustically perfect and one of the most luxurious on the south coast. On this particular night the vast auditorium was packed with a most enthusiastic audience and the band was in wonderful form. "It was just one of those nights when we all felt good", remarked Pat Halcox afterwards. A glance at the tunes will show just how varied is the band's repertoire – blues, marches and jazz standards, all are within the Barber field, and all come in for individual treatment. Ottilie's songs, for instance, include a spiritual – Strange Things Happen, a jazz classic – Pretty Baby, and two blues songs – Georgia Grind and that beautiful number, Careless Love. Miss Patterson has been praised by such great blues singers as Big Bill Broonzy, Brother John Sellers, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that she is one of the very few white singers who can sing Negro folksongs without causing acute embarrassment to the listener. That such a rich and colourful voice should come from such a petite and retiring person is a constant source of wonder. The band's contribution to this record reveals them at their best; the Dome has always been one of their favourite dates. Opening the programme with Bugle Boy March, an old favourite of New Orleans marching bands, the boys next give us a charming version of Wilbur de Paris's composition Majorca. The first half of the concert ended with a swinging version of Duke Ellington's Rockin' in Rhythm. Those who were at the show will be delighted to find it included here. My Old Kentucky Home is the famous old song by Stephen Foster – a very different version from the original! The concert finished with that good old standby Mama Don't Allow. This is a rousing rendition with Chris singing the well-known lyrics. I like to think that if the ghosts of the Prince Regent and Madam Fitzherbert were wandering around the Dome on this particular night they, too, were tapping their feet and nodding approvingly to this gay and carefree music. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee: Sonny, Brownie And Chris (1958)

Notes by Paul Oliver "In our Skiffle groups we tried to play the folk music of the American Negro. Here are two of the great folk and blues artists who created the music we were attempting," said Chris Barber as he introduced to packed halls throughout Great Britain a smiling, light-skinned Negro who walked with a limp, and his tall, darker, blind companion: Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry. Possibly only a small proportion of those responsive audiences were really familiar with the work of his two guests and none could have foreseen the thrilling experience that their music and song was to provide. A score of years of close partnership which has brought them from the dust roads of North Carolina to the bright lights of Broadway has enabled them to achieve an incomparable personal and musical harmony in which the simplicity of their folk origins has been retained whilst their techniques have been perfected. No one who heard them in person will forget Sonny Terry's crying, wailing, singing harmonica, his fluttering fingers and cupping hands, his whoops and hollers as he played and the sudden smiles that lit his otherwise impassive dignified features. Nor will they forget the disarming dexterity of Brownie McGhee's finger picked guitar work at once rhythmic and melodic, that warmth and feeling for his music which was expressed in every movement that he made. Sanders Terrell -- SonnyTerry -- was born on his father's farm in Greensborough, Georgia on October 24th, 1911. His father played harmonica and Jew's harp and taught him to play these instruments, an education which was to stand him in good stead when two accidents when he was eleven and sixteen years of age rendered him almost completely blind. As a child he used to sing in the Hester Grove Baptist Church -- rocking Gospel Songs like This Little Light of Mine, and these he played on his harmonica when he begged in the streets. He worked in medicine shows, attracting the crowds with his singing and playing and with his "Buck and Wing" dances which he can still be persuaded to perform. Then in 1933 he joined the famous Blind Boy Fulleer -- Fulton Allen -- a folk guitarist and blues singer who worked the Carolinas in the company of George "Oh Red" Washington whose spirited washboard playing is to be heard on many of his records. Fuller had a varied repertoire which included I Want Some Of Your Pie, a blues which Sonny adapted as Custard Pie, his favourite song. The owner of a Durham department store J. B. Long acted as Fuller's manager and secured for the musicians a number of recording dates. News of J. B. Long reached Brownie McGhee via his harmonica player Jordan Webb and the two musicians finally met in Burlington in 1937. Baptised Walter Brown McGhee, Brownie was born in Knoxville, Tennessee on November 30th, 1915, the son of a farmer and levee worker. An attack of polio at the age of four affected the growth of his right leg and the partial incapacitation caused him to devote much of his time to the piano and the guitar, which he played at the Solomon Temple Baptist Church in Venore, the township where he went to school. Later he sang in the Sanctified Church and in the Golden Voices Gospel Quartette: spirituals like Glory and If I Could Only Hear My Mother Pray Again which latter he was to record as by the Tennessee Gabriel. Leaving school after Ninth Grade he decided whilst still in his early teens to earn his living by playing and singing. In Minstrel Show and Carnival, roadhouse and juke he performed, wandering from Tennessee to Virginia and the Carolinas, adding blues-ballads like Betty and Dupree (Diamond Ring) to his rich store of folk songs and blues. When he met Sonny Terry and Blind Boy Fuller he was a folk singer of repute in spite of his youth. Fuller died in 1941 but by this time Brownie and Sonny had joined forces. Both moved to New York; Sonny to participate in the December 1938 "Spirituals to Swing" concert, Brownie to visit his mother. Both lived in close association with the great Leadbelly, worked together and in the company of such blues artists as Buddy Moss and Champion Jack Dupree, appeared at concerts and folk song festivals and performed together or separately in stage productions including "Finian's Rainbow" and "Cat On A Hot Tin Roof". The maturity of their partnership is well demonstrated on Key To The Highway on which they play the form of blues that they have introduced to countless thousands of people through the years. They are not jazz musicians, but it was Chris Barber's Jazz Band that enabled them to bring their music to British audiences and it is fitting that the band should provide the accompaniment on this, their first British recording -- a record which will serve as an excellent introduction for those jazz enthusiasts who have yet to explore the rich field of Negro folk songs. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber Band Box, Volume 1 (1959)

Chris Barber, together with his Jazz Band and singer Ottilie Patterson, forms one of the phenomena of post-war Show Business. Playing a music that, ten years ago, was considered by the bookers lucky to have an audience numbered in hundreds, he leads today a band which has proved itself the biggest musical draw in Britain. Having displaced the big swing bands, the Latin-y locals, the treacle-tuned dance bands and all other hot groups in the battle to win the public's favour, the Barber band proceeded, in 1957, to sell in this country the equivalent of close on a million 78 rpm discs. At the beginning of 1959, the band's record of Petite Fleur – a clarinet speciality featuring Monty Sunshine – had alone sold more than this number of copies, after roosting in the German Top Ten and fighting its way up to No. 2 in the fiercely competitive American Top Hundred sellers, besides getting into Britain's top five pops. Not bad going for a traditional trifle making no concessions at all to commercialism! In Britain, the band is assured of a sell-out whenever it appears at clubs, concerts or dance halls, and of maximum audience reaction at every radio and TV "Exposure". Chris and Ottilie, as solo guest stars, were invited to Denmark in 1952 and Holland in 1955 respectively – and the band as a whole enjoyed enormous success in tours of Denmark in 1954 and 1958; of Holland in 1956,1957 and (twice) in 1958; of Sweden in 1958, and of Germany in 1958 and again this year coincidentally with the issue of this record. In addition, an immensely successful American tour of major dates in February and March of 1959 made it only the second band (and certainly the first ever traditional jazz group) to reverse jazz history and make the East-West Atlantic crossing! What, then, is the formula for this success? How has what was once a minority appeal music come to be so formidable a force in the entertainment world? One vital quality made this possible. Enthusiasm! Enthusiasm it was that inspired Chris Barber to form his first band in 1949, when he was still an apprentice actuary with an insurance company. It was fiery enthusiasm that drove him to give up his safe career in the City and turn professional musician to play the King Oliver music he so much admired; that permitted him to go through an agonising reappraisal and disband that first successful group because, in the end, he found the rigidities of strict New Orleans style too confining; and that enabled him to form another which, through many ups and downs, finally boosted him and his music to the position it holds in the business today. It was the same quality of excited awareness that encouraged him to take on, in 1954, the then unknown singer from Northern Ireland, Ottilie Patterson, with the unshakable conviction that she would (as she did) soon win for herself a star position with the emotional impact of her singing. And it was enthusiasm again that prompted Chris to pioneer in this country the production of long-playing records taped "live" from concert appearances – so that the disc buyers could share with the audiences in the theatres that urgent immediacy, superb sense of showmanship and sheer creative excitement which is so peculiarly the Barber band's own. "On this record, as on most of the LP's we ever made", says Chris, "we have tried to strike a balance of all the kinds of music we cover – a canvas that, from the jazz point of view, is as broad as we can find. This enables us to find an outlet for all types of playing, for we don't restrict ourselves to one example of the music: we'll play anything, if we think it sounds nice when we play it! "The music on this disc thus ranges from 1904-1905 ragtime to 1958 Count Basie work; from early vocal vaudeville jazz to such modernities as John Lewis's Golden Striker. Monty plays a new Sidney Bechet number, Si Tu Vois Ma Mère; we managed to persuade Ottilie to make one of her rare visits to the keyboard to accompany herself on Squeeze Me because we think she plays pretty good piano. "We put in the old Jay C. Higginbotham-Henry Allen speciality Give Me Your Telephone Number. We play Swanee River (Jive Around Stephen Foster if you like!) and there's even the Mary Martin number from 'South Pacific', I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Out Of My Hair, in there…" No trombone specialities? "Not really", says the diffident Mr Barber. "I prefer to get my kicks more on the arranging side. There were some quite tricky problems here. Hot House Rag, for instance, is a transcription from a piano rag to a band piece. So, in its very different way, is Golden Striker. Both of these, as you can imagine, presented some difficulty." Both of them, however – like every single track on this record – are successful; both go like a bomb; both swing; both are entertaining ... and both display, in nicely judged proportions, that verve, élan, zest or what you will, which, coupled with its unerring sense of jazz rightness, makes Chris Barber's Jazz Band deservedly the most popular in the country. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band with Ottilie Patterson: Chris Barber International, Volume 1, Barber In Berlin (1959)

Notes by Brian Nicholls Just across the road from the point where the grandstands loom over the Avus motor circuit in Berlin; where the roar of engines on the fastest race track in Europe held the Berliners in a grip of excitement at this year's German Grand Prix, stands the Deutschlandhalle – a vast stadium cum concert hall. Here it was that these recordings were made. I describe the Hall's position as Chris Barber describes it, not as in the normal city guide. Whereas you or I might give directions using pubs as landmarks, Chris orientates himself by means of the nearest motor racing circuits. And he confides sadly that the band was in Berlin only for a concert – and not the motor racing – on this memorable one night stand. The Deutschlandhalle is rarely filled, for it seats a comfortable 12,000; yet for this night it was sold out completely in advance; and the audience included 3,000 East Germans who had crossed the border to see the band. The huge oval loftiness was filled with a suppressed and intense excitement as the start of the concert approached. In the vast central arena space, the seats filled quickly, and in the high banking to the roof, a sea of faces focused on the diminutive stage. Behind the scenes, Chris, imperturbable as usual, changed and warmed up and cracked schoolboy jokes with the rest of the band. Out front, another Briton who had travelled to Berlin for the concert was anything but unperturbed. Joe Meek, the balance engineer, had problems. Because of the size of the hall, the setting up of a detached, off-stage recording studio would have necessitated over 300 yards of cable for each microphone and a lack of contact with events on the stage that would have made serious recording impossible. A snap decision was made, and Joe and Peter Willemoes took over four seats alongside the stage, hoping to balance by ear and capture the atmosphere from a seat in the stalls. Their worries were increased by the fact that no rehearsals were possible – for one of the attendants had seriously damaged Dick Smith's bass carrying it through the hall, and the period set aside for rehearsals had been occupied by a frantic search for replacement of the instrument. The appearance of the band on stage, and the roar of welcome that opened the show was therefore a moment of some apprehension for Joe Meek. But the measure of their success can be judged from final recording quality. Joe comments only that he ended the evening with the worst (technical) headache yet known in the history of mankind! Probably the atmosphere of the occasion seeped through the floors and walls of the concert hall to the band's changing rooms, for they opened the concert with a punch and intensity that usually comes only after a tentative warm-up number. Climax Rag came romping into the Deutschlandhalle with a sudden and unexpected impact that unified audience and band from the first few bars. From that moment, the hall came alive, and every number lifted to a peak. As Chris admitted later, "The second half of the concert had to be an anti-climax by comparison. It all happened before the interval, when everything we tried came off and each number was full of those small moments of rapport that usually come only a few times in a session". What you will hear on this disc is an almost complete transcription of that memorable first half – with the stark simplicity of Ottilie's unaccompanied start to Easy Easy Baby; the beauty of the chimes in King Oliver's classic piece; the tremendous rocking beat of Gotta Travel On; and, above all, the dynamic playing of Pat Halcox. This was the "on-est" of his "on" nights, and he emerges here as an exceptional trumpet player by any standards. I think you will enjoy this disc, for it captures the heat and emotion of a tremendous concert. Apart from this, however, it is the latest recording of Chris and his Band at work. In a group where the standards are continually rising and where improvement is a natural joint endeavour, the latest recording is synonymous with the best to date. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber Band Box, Volume 2, Elite Synopations (1960)

Here is the foundation of all Ragtime. Here is the genius whose spirit, though diluted and polluted, was filtered through thousands of cheap songs and vain imitations which have done much harm to the reputation of the real classic Ragtime. These numbers are the American Creation and the marvel of musicians in all civilized countries. They are NOT NEW and they NEVER will be OLD. The oftener they are heard the better they are liked. SIDE ONE SWIPSY CAKEWALK (Joplin & Marshall) — Fine. But don't take our word for it. Hear it. BOHEMIA RAG (Lamb) — Inimitable. The melody glides through a labyrinth of harmony with a surprise at every turn. A classic. ELITE SYNCOPATION (Joplin) — The syncopations in the last part are actually frenzied. COLE SMOAK (St. John) — Cole Smoak is a positive inspiration. Human language is not equal to the task or painting the interior thoughts of the soul. It is also certain that all souls do not slake their thirst from the same fountain. This number appeals to the writer in language unutterable. Would be pleased to hear from any who have heard the echo. ST. GEORGE'S RAG (Barber) — This is a fancy flight of a cultured musician into the realm of popular taste. He has hooked the rabble wagon however to a star and moved the procession toward a higher peg. It is to your credit if you like St. George's Rag. SIDE TWO THE PEACH (Marshall) — Nothing finer. Intelligent and snappy. THE FAVORITE (Joplin) — No abatement of demand. There will be a temporary stop to its sale when every family in the civilized world has a copy. REINDEER RAG (Lamb) — Corrugated to a finish. Exhilarating. THE ENTERTAINER (Joplin) — Joplinese and eccentric. Away up. GEORGIA CAKEWALK (Mills) — Profound as Beethoven and thrilling as a country fiddler. Compared to others, like an oasis in a dreary desert of piffle. CHRIS BARBER WRITES: Ragtime is a musical idiom that was popular between 1895 and 1920 (having no connection whatsoever with a bandleader named Alexander!). It had a very great influence on jazz development but has been sadly neglected in recent years. We had the honour of visiting New Orleans to give a concert in 1959, and we were fortunate to find a collection of original Ragtime sheet music at Bill Russell's little shop in the French Quarter, thus enabling us at last to prepare and record some authentic Ragtime-style jazz. All the numbers on this LP except Georgia Cakewalk and St. George's Rag come from this collection. The descriptions of the tunes, the illustration and the panel underneath the title are all taken from the original Stark Publishing Co. sheet music, as is the cover of "Elite Syncopations". |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber International, Volume 2, Chris Barber In Copenhagen (1960)

Notes by Tony Standish "I'm crazy about that band, that's a wonderful band... those cats wail just like coloured people." Thus Muddy Waters, expressing an unsolicited opinion on the music of Chris Barber's Jazz Band. Muddy meant it – but there was a note of puzzlement in his voice, as if he could hardly believe that such a thing was possible! After all, Muddy Waters is one of the great blues singers – a Negro from the State of Mississippi whose background is that of American Negro music; to Muddy, as to the Negroes of New Orleans, jazz and the blues came naturally: a unique music created by ordinary people in unique circumstances. But Chris Barber and his fellow musicians are young, middle-class, white and British. The environment in which they grew up could hardly have been more different to that experienced by the Negro working man in the Deep South. Yet Chris, and thousands like him, have learned to play in the Negro's musical idiom with conviction and authority, and their accomplishments have been recognised by men like Muddy Waters, Paul Barbarin and many other veterans. The folk music of one culture has thus been successfully transferred to another until, not only in Britain but in the entire Western world (and going East fast), the musical styles of the American Negro are functioning in a folk music capacity. From Melbourne to New Orleans to Copenhagen, the name of Chris Barber has come to symbolize this new-old music – not only to teenagers but to intelligent people of all ages and from all walks of life. Finding little or nothing that speaks to them or for them in mass-produced "popular" music, they have discovered in traditional jazz a music which has simplicity and which deals straight from the heart in honest, direct and wholesome emotions. Joy and sadness are universal and in a world which for the most part has no folk music of its own, but needs one, Chris Barber's blues, stomps, rags and standards have found a willing and enthusiastic audience. Such an audience is the one which applauds so vociferously here. That everyone who gathered in Copenhagen's K.B. Hall on March 1st, 1960, was enjoying himself is immediately obvious from the fire and vigour of the music and the quick, responsive roars of approval from the fans. Beginning with the fast-paced Market Street Stomp and continuing through the meditative and brilliantly expressive Blue Turning Grey until the last rollicking strains of High Society, one can sense a feeling of rapport between performers and listeners – an atmosphere of give-and-take which is seldom achieved in the formality of a recording studio. The musicians are relaxed, and what they are saying is being heard, so they say it vehemently, with more conviction than they might otherwise command. Pat Halcox is the model lead trumpet – one of the best in the world – balancing perfectly his role as a member of the ensemble against his considerable talents as a solo improvisor. Alongside him, Chris and Monty are satisfying amalgams of a variety of influences, with Ory and Jim Robinson (Chris) and George Lewis (Monty) forming cornerstones on which they have built, adding and modifying, until two individual styles have emerged. And, beneath the front line, the rhythm throbs industriously, propelled by Dick Smith's pumping bass. The end product is a hot, thrilling and, happily, infectious jazz sound – six cats wailing like coloured people ... |

|||

Ottilie Patterson with Chris Barber's Jazz Band: Chris Barber's Blues Book, Volume 1 (1960)

Notes by Chris Barber I've heard the Blues in Mississippi, The Press were equally struck by the incongruous blend of Ireland and the Blues. The San Francisco Examiner captioned Ottilie's photo "The World's Only Irish Blues Singer", while another San Francisco paper enthused on Ottilie's broad Southern States accent. In New Orleans, that same year, the "States and Item" claimed that she could "wail like a New Orleanian". "Yes the Blues sure do get around." At Muddy Waters' club "Smitty's Corner", at 35th and Indiana, Chicago, the audience shouted for Ottilie to sing with Muddy's Band – a far cry from that students' dance in 1949 at the Belfast College of Technology, when she first heard Teddy Bunn's If You See Me Coming rendered by trombonist "Wild" Al Watt, startlingly dressed in white pants, red and white striped blazer and straw boater. That was Ottilie's first introduction to the Blues, quickly followed by lunchtime tuition in Boogie Woogie piano from Derek "Haggis" Martin – another student at the college. In the deserted club room of the C.I.Y.M.S. (Church of Ireland Young Men's Society) Ottilie absorbed the Blues and learnt the rudiments of Blues piano accompaniment. Yes they even made the scene with the Wearers of the Green. When Al Watt and Derek Martin formed a band in August, 1952, Ottilie joined it automatically, for these three were a dedicated trio. To Ottilie, the "Muskrat Ramblers", as the band was called, was a chance to sing only the pure Blues – something for which she had formed a taste during her debut with the Jimmy Compton Band in the previous year. Alas, the demand for jazz was small and the Muskrat Ramblers broke up. Ottilie came to London, Al Watt stayed at home and Derek Martin found his way eventually to San Francisco where he accompanied Lizzie Miles. In London, Ottilie met Beryl Bryden, who in turn introduced her to the Chris Barber Band. Yes the Blues sure do get around. In those early days, Bessie Smith's records were the greatest single influence on Ottilie's singing; but it wasn't long before her own natural feeling for the Blues caused her to turn to the more basic Blues styles of the last twenty years for inspiration. The mood of the Twenties, which Bessie captured so magnificently, expressed itself in an idiom that, in terms of 1961, is anachronistic. A natural love and understanding of the Blues led Ottilie to the idiom of today, but, even in the first months of working with the band, the beloved songs of the Empress of the Blues were given a very personal treatment. The critics who complained that she copied Bessie too closely obviously didn't examine her singing in any depth, or they could hardly have failed to notice the personal inflections and the individual stamp. The tunes on this LP range in style from the old fashioned majesty of Backwater to the R & B idiom of Ruth Brown's It's All Over and Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean. Blues Before Sunrise is nearly as old as Backwater, yet nearer in origin to the Folk Blues, whilst Kid Man Blues was originally sung by Big Maceo – the favourite pianist of all the early Blues singers; Memphis Minnie wrote Me and My Chauffeur and Can't Afford To Do It – the latter being played here in the style of the Harlem Hamfats – a band led by Minnie's husband, Joe McCoy. Jim Jackson's K.C. Blues gave the world its first recording, in 1930, of many now famous couplets, and Trixie's Blues is, of course, the composition of Trixie Smith. Four Point Blues was specially written by our great friend from Chicago, St. Louis Jimmy, and the set is completed by two originals from Ottilie – Tell Me Why and Bad Spell Blues. Both are dedicated to Muddy Waters, whose singing with his band at Smitty's Corner was such an inspiration to us. A living proof of the immortal vitality of the Blues. |

|||

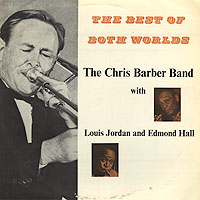

Chris Barber's American Jazz Band (1960)

Notes by Charles Fox Coals, the Elizabethan proverb assures us, should never be carried to Newcastle. Similarly, so plenty of our contemporaries are wont to argue, it would seem madness to export jazz to America. Proverbs, though, have a habit of becoming outmoded, and this newly-minted paradox (to swop metaphors in midstream) is getting rather tattered. One has only to consider the reception given to British bands in the United States during the last two or three years to see that. What is really rare, however, is for a British jazz musician to visit the U.S. and there – with the full blessing of the American Federation of Musicians – to make records with a band of his own choosing. Spike Hughes did it back in 1933. So did Nat Gonella six years later. But since then – with the rather special exception of Ken Colyer's private recordings in New Orleans – there has been nothing. Nothing, that is, until Chris Barber produced this album. "Years ago, when I was listening to the great American jazzmen on record," Chris wrote recently, "I used to daydream about the record sessions I would organise: which trumpet player I'd match with what clarinettist; the rhythm section I would use with various front-lines." And Chris finally got his chance to make this particular daydream come true when he was in New York in 1960, at the end of a successful tour of America with his regular group. One of his first choices was Sidney de Paris, best known today for his work with the band led by his brother, Wilbur, but in fact a trumpet player of extremely wide experience, a mainstay of the old Don Redman and Benny Carter orchestras as well as a veteran of 1920's small group jazz and star of numerous recording sessions in the 'thirties. The clarinettist is Edmond Hall, a jaunty, almost capricious performer who, for nearly four years, was one of Louis Armstrong's All Stars. More recently a starred player in American club jazz, Hall is another musician who spent most of the 1930's in a big band – in his case, Claude Hopkins' orchestra. Hank Duncan might be termed a lesser-known pianist, for although an active jazzman since the late 'twenties, he has been heard on few records. A vigorous exponent of the Harlem, or "stride" style, he plays consistently well throughout this LP, whether he's taking a solo, backing up Sidney de Paris's singing, or just keeping the rhythm section firmly in hand. Hayes Alvis, on bass, worked both with the Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington orchestras and, at the time this record was made, was a member of the Wilbur de Paris band. It was Chris Barber's original intention to complete the band by using Jellyroll Morton's old drummer, Tommy Benford. But Benford, it transpired, was up in Boston, so Hayes Alvis brought along Joe Marshall, the drummer who took Jimmy Crawford's place in the Jimmie Lunceford orchestra and who later played with Johnny Hodges' band. One of the noticeably good things about this disc is the trombone playing of Chris Barber himself. In this distinguished company he slips in some solos that must be as shapely and relaxed as anything he has ever put on record. The whole atmosphere of the music, though, is relaxed; its pattern not really tied to any particular style or period of jazz. The material, too, covers a wide field, ranging from Ma Rainey's See See Rider to the 1930 film tune, Sweethearts On Parade, including en route two examples of Spencer Williams' handiwork: Tishomingo and Baby, Wont You Please Come Home?, the latter written in collaboration with Clarence Williams; and also Down Home Rag, a composition by Wilbur Sweatman, an early Negro bandleader who won some notoriety through his ability to blow four clarinets at one time. "I think we were all happy with the results," says Chris Barber. "Sidney de Paris even started strutting round the studio as his own 'Second Line' during the playback of Tishomingo Blues. Certainly this session gave me as much pleasure as anything we did on that American trip. But, after all, there's something wonderfully satisfying about turning a dream into reality." |

|||

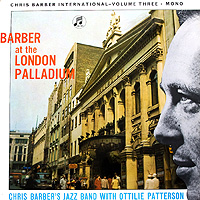

Chris Barber's Jazz Band with Ottilie Patterson: Chris Barber International, Volume Three: Barber At The London Palladium (1961)

Notes by Brian Nicholls This was a concert where the Band, the audience, the recording equipment and even the theatre (if this is possible) rose to the occasion. The London Palladium holds a kind of mystic excitement within its walls and ice cream-impregnated carpets, an excitement that can inspire or crush a performer. Just which it is to be depends entirely upon the stature of the performer. It is the best, and the most experienced, who overcome their nerves. They are faced by a sea of banked faces, a mental hangover from the advance publicity, and, ultimately, by the shattering efficiency of the technicians whose easy mastery of the huge stage highlights the slightest nervousness. So the Palladium starts one-up! Accordingly, the decision to hold the Jazz News Poll Winners' Concert there was a tricky one. Poll Winners' Concerts, as a whole, tend to be tricky anyway. After all, jazz is a sensitive art form, hardly encouraged by the demands of a do-or-die "go-out-there-and-prove-you're-the-best" type of occasion. However, since the Barber band romped home as winners of the Poll, everything was made easier; this, after all, is no ordinary band. At worst it is completely efficient; at best it is superb. And so it was that Phil Robertson, the band manager, opened the concert on Good Friday last. Unfortunately, his attempt to use the "Demon King" Trap was foiled by the management, and he had to come on from the wings! We were standing there with our fingers crossed. Then, too, Chris had invited Joe Harriott to sit in with the band. This was a surprise and, at first, the sound was even a trifle awkward. Then, suddenly, the front-line parts fell into place. From the viewpoint of someone standing at the back of the stalls – where I was for most of the concert – two numbers stood out. First, there was the duet between Joe Harriott and Ian Wheeler on 'S Wonderful; then there was the full band version of Joe's composition, Revival. 'S Wonderful, I think, brought a realisation of Ian Wheeler's true stature. Matching each other, phrase for phrase, their duet was magnificent, a real show-stopper. When I wrote the sleeve notes for the Berlin LP, I suggested that it was "Pat Halcox's disc". Well, this, I feel, must be called Ian Wheeler's disc. Yet, on reflection, this seems unfair to the complementary team of star musicians – and especially unfair to Chris. This concert was, after all, a tribute to his sincerity, to his ability. The programme demonstrates the range of his musical ambitions, the targets he has set the band. It also proves the completeness of his success. In fact, as a programme for a Poll Winners' Concert, it could hardly have been bettered. Here is a thorough demonstration of the Band's capabilities. Spirituals such as Lord, Lord, Lord lead to the New Orleans stride of Fidgety Feet, to Ottilie's slow blues, Too Many Drivers, and to the Swing Era 'S Wonderful. Then, through Ellington – Creole Love Call – to Joe Harriott's Revival. This is where Traditional and Modern Jazz really come together. Looking back on this show, I find myself impressed more and more by the growing maturity of Pat's trumpet lead. Tense, yet quiet, he holds the band on Creole Love Call. But, when he wants to, he can play really explosive solos, full of punchy, dynamic phrases. Then there is Graham Burbidge's bass drum work on Just A Little While To Stay Here. This is the way he heard a street band drummer play when last the band visited New Orleans. What else need be said? Oh, yes. The extraneous voices, before, between and after numbers, in order of appearance, belong to Phil Robertson, Chris Barber and Jazz News Editor John Martin. I was the fourth scream from the left at the end of 'S Wonderful. |

|||

Chris Barber's Jazz Band with Ottilie Patterson: Chris Barber Bandbox, Volume Three: Best Yet! (1961)