|

|

|

|

| Brian Rust's Sleeve Notes | |

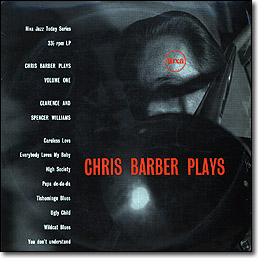

The eight numbers presented on this record are all composed by, or associated with, the two unrelated Williams' from New Orleans, Clarence and Spencer. Spencer, the elder, was born in 1888 and Clarence ten years later. Both have written many successful popular songs, but it is as jazz composers that they are best known. Spencer lived for many years in England, in Paris, and when last heard of had settled down in Sweden. Clarence, on the other hand, has never left America; at present he owns an antique shop in Harlem. Spencer has made comparatively few records, while those for which Clarence was responsible run into many hundreds. You Don't Understand is a collaboration between the two Williams' and James P. Johnson, one of the doyens of the Harlem school of jazz piano. The number was written in 1929, and is in the form of a conventional thirty-two bar popular song. Tishomingo Blues, named after a Southern township, was first recorded in 1928 by Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra. The melody is in the blues idiom, though it does not follow the traditional twelve-bar form. In Wild Cat Blues we have an example of Sidney Bechet's work as a composer. He recorded this number as a member of Clarence Williams' Blue Five in 1923. Ugly Child was written as a parody by George Brunis, pioneer white New Orleans trombonist, on a song composed by Clarence Williams in 1916 -- Pretty Doll. Ottilie Patterson sings the parody with tongue-in-cheek humour. Everybody Loves My Baby has been a standard vehicle for jazz bands and commercial groups alike since it was written in 1924 and first recorded by Clarence WiIliams' Blue Five, with Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet. |

|

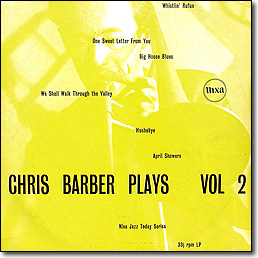

Our opening number, Whist1in' Rufus, is one of the oldest tunes in the Barber repertoire. It was written in 1897 by Kerry Mills, a white composer of popular marches and cakewalks such as At A Georgia Camp Meeting and Red Wing. It had a great vogue in late Victorian and Edwardian England, long before the arrival here of Tin-Pan Alley's conception of ragtime. The great banjoist Oily Oakley recorded it in London in 1903 to the piano accompaniment of Landon Ronald, but by its nature it lends itself to treatment in the jazz idiom, with comparatively little solo work, relying more on ensemble passages to give the period flavour of an old-time dance band. Big House Blues is one of the lesser known numbers associated with Duke Ellington, whose band recorded it in 1930 under the pseudonym of "The Harlem Footwarmers". It is a slow, moody, rather eerie piece in the idiom of The Mooche; Pat Halcox plays a growling muted comet solo following the lead given by such masters of the style as Bubber Miley and Cootie Williarns, and Monty Sunshine sounds very much like Bamey Bigard, who was Ellington's clarinettist on the Duke's record. The tune April Showers is usually associated with the late Al Jolson, who first introduced it in his show Bombo in New York in the autumn of 1921. It became a hit at once, and has passed into the category of standard popular numbers following several recordings by Jolson himself and by numerous dance bands such as Paul Whiteman's. It is very rarely heard as a jazz vehicle, however, and each member of .the front line has a long solo in which to work improvisations that are really fresh. One Sweet Letter From You was composed in 1927 as another popular tune, this time by Harry Warren, hero of hundreds of melodious and catchy numbers from Pasadena in 1924 to September In The Rain in 1937, and many more before and since. Kate Smith and Sophie Tucker each recorded it, each accompanied by a Red Nichols group, and there were again hosts of good, bad and indifferent straight dance versions at the time when it was a "plug" number. In 1945, the great New Orleans comettist Willie "Bunk" Johnson made another recording, without lyrics, and since then it has been adopted as a standard jazz piece by traditional bands the world over. Monty Sunshine is the soloist in his own charming Hush-a-Bye in which, accompanied only by banjo and string bass, he plays effortless variations on a most attractive melody. Though tender and sweet, it never cloys; it has sentiment, but no sentimentality. Lastly, We Shall Walk Through The Valley is a traditional spiritual sung by Dick Bishop, one of the members of Lonnie Donegan's Skiffle Group. It begins slowly and in a sweetly sad strain, but after a few bars the band strikes up with a rousing march, which suggests that the number was originally one of the "funeral parlour" repertoire like Oh, Didn't He Ramble? Its simplicity and directness are worth a hundred wordy sermons. |

|

Thriller Rag is an early number, sometimes credited to one May Auferheide. It has a beautiful archaic melody of which the band makes the most. There are scores of ragtime numbers like this, dating back beyond the turn of the century, which seldom receive attention; it is thus particularly to the credit of the Barber band that they include such material in their repertoire. Texas Moaner is a 1924 composition by a rather obscure New York blues artiste named Fae Barnes, who recorded for Paramount during that year. She did not record this number, so far as is known. Laura Smith did, however; also Eve Taylor -- the latter in the august company of Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet. It is an attractive blues theme. Sweet Georgia Brown, a Tin Pan Alley creation of 1925, has always been a favourite jazz standby. Ben Bernie gets credit for having written it, and he recorded it with his Hotel Roosevelt Orchestra at that time, with Jack Pettis, late of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, in the reed section. On this recording Chris Barber is featured solo, with much of the shouting timbre of a J. C. Higginbotham in his phrases. Mention of Jack Pettis brings us to Bugle Call Rag, which Pettis recorded with the original Friars Society Orchestra in August, 1922. (He later made another version, in May, 1929; both were labelled Bugle Call Blues.) Since those early days, it has been the victim of every commercial bandleader's whim, notably Harry Roy's, and has also been attempted by other entertainers from cinema organists to mouth-organists. It is good to hear it well-recorded by an intelligent jazz unit. Note especially the three voices of the front line in the coda. Sidney Bechet, composer of a hundred attractive melodies, has, in Petite Fleur, a true Creole tune, one of his happiest inspirations. Monty Sunshine acknowledges the composer gracefully, and there is a neat bridge passage for Dick Bishop's guitar, sounding rather like a zither and lending a wistful air to the performance. The last number dates back to 1921. Wabash Blues, quite a creditable commercial blues, is another long-established favourite in the jazz repertoire. It was used as a theme tune for a New York production of the period, "Rain", and has been recorded by a gamut of bands, from the Benson Orchestra of Chicago to the Charleston Chasers. |

|

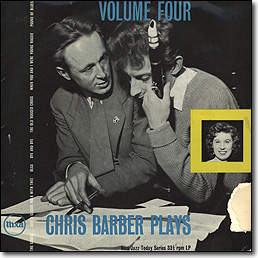

Out of the total of seven titles, three are sacred music, yet even the sternest theologian could hardly take exception to the tender simplicity of Old Rugged Cross, that favourite nineteenth-century hymn, played as Monty Sunshine does here. With only the slightest variation on the melody he transports it from being just another song of praise to being a reverent musical experience. When the Saints Go Marching In is far too often heard pounded out at a viciously monotonous tempo, but here, complete with lyrics that give meaning to the performance, we have as fine a version of this enormously popular jazz favourite as has ever been heard. No-one knows exactly when it originated; the Kentucky hill-billy singers Frank and James McCravy have laid claim to this, but the truth will probably never be known. Just A Closer Walk With Thee is a true Negro spiritual, brought to our notice first by George Lewis, the veteran New Orleans clarinettist. Here again, we have a relaxed, slow tempo with lyrics sung as sincerely as anyone could wish, with a doubling-up of tempo to finish with. Of the secular numbers, the Barber band produces a composition of originality and charm in Pound of Blues. Slightly Ellingtonian, with the merest suggestion of modernism, this is one of the few examples of how jazz can sound fresh and new within the so-called "traditional" framework. (It really is about time we stopped labelling our jazz music, or at least, that we applied the correct labels. Surely the truth is that music is either jazz or it's not, and if it's jazz, then it's either good or bad jazz. This is a good jazz, and it can safely be left at that. It sings, it swings, it has all the oft-quoted Morton ingredients and yet it does not sound as though it had been raked up from the remote corners of some museum.) The two colossi of what, if we are to keep labels, should be termed "mainstream" jazz, King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, were each responsible for one of these two numbers: Olga (introduced by Oliver in 1930) and Bye and Bye (introduced by Armstrong in 1939). Olga was originally recorded by Joe Oliver in May 1930, and has not been re-made by anyone since. It is offered here with a suggestion of the Duke, as well as the King; a fine relaxed piece of jazz, like Oliver's own. Then we have When You And I Were Young, Maggie. Originally a rather morbid drawing-room ballad of the type that enjoyed a great vogue during the 'seventies and 'eighties of last century, it must have been attempted by countless singers, singly and in duets, trios and quartets in the intervening years, until Mezz Mezzrow smartened it up and showed the world in 1938 what a potent bit of jazz it could be. Monty Sunshine's version is nothing like the original presentations, of course; he examines the theme from all angles, never runs out of ideas and never bores the listener. Which may be safely said of this entire presentation. |

|