George Melly on Revivalist Jazz,

Skiffle, and the Trad Boom

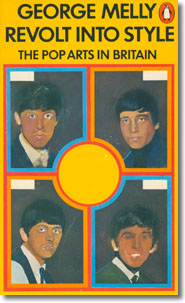

In addition to his highly entertaining Owning Up, a jazz autobiography of his years with Mick Mulligan, George Melly published a Penguin book on British pop culture in the 1950s and 1960s, Revolt Into Style: The Pop Arts In Britain (1970). The following excerpts summarize what Melly had to say about the jazz-oriented aspects of the music scene, with several comments about Chris Barber's pivotal role in it all.

Revivalist Jazz

It was inevitable that the spontaneous if mysterious enthusiasm which sprang up all over wartime Britain for an almost forgotten music, Negro jazz of the 20s, should lead eventually to an attempt to reconstruct the music and, by the end of the war, there was already one established band, the George Webb Dixielanders. Within a year or two the revivalist jazz movement had spread to every major city in the British Isles, and it was in the jazz clubs of the late 40s that what might be considered the dry-run for a pop explosion first took shape.

Yet I don't think that the revivalist jazz movement qualifies as a pop movement proper. I have written elsewhere and at length about those days but feel that, to justify my qualifications, I must at least make an inventory of my reasons for excluding it from the pop canon despite the many points of similarity. Revivalist jazz shared with the later pop movements its spontaneous generation with no initial commercial encouragement: the invention of a life-style through which it expressed not only its own identity but its contempt for outsiders; its eventual decline due to its success with a wider, less perceptive public and the resultant lowering of standards and over-exposure.

Where it differed was in the way it looked back towards an earlier culture for its inspiration, thus admitting that it believed in a 'then' which was superior to 'now' - a very anti-pop concept. What's more both its executants and their public were mostly into their twenties before the movement was even under way and, although this was the result of the war, it did tend to add a certain ballast, a potential respectability. This was further underlined by the fact that, although enthusiasm for the music cut right across the social spectrum, it contained a surprisingly large minority of middle- and upper-class adherents and even a few elderly and distinguished advocates who had formed a taste for the music before the war. In consequence, right from the off, the press treated it as an eccentric rather than a scandalous manifestation. There was none of that snobbism disguised as moral concern which was later to be levelled at the essentially working-class pop movements which replaced it. This was partially because the sexual emphasis was absent. Jazz may have begun as brothel-music, may have provided the background to the prohibition years, but the atmosphere of the British revivalist clubs, while permissive enough by the standards of the time, was jolly and extrovert rather than orgiastic. It's true that a musician of strong sexual appetites 'did all right' and that virgins were thin on the ground, but there was no moment when the sexual potency of a revivalist jazz hero made it necessary to isolate him from his over-stimulated fans.

On balance then I feel that the antiquarian, post-adolescent nature of the British revivalist jazz movement of the late 40s destroys its claim to being thought of as a pop movement. Despite its large public it was never even fully exploited. A series of over-long, over-packed concerts, the defection of Humphrey Lyttelton, and the emergence of the 'traditional' purists were enough to sink it.

Skiffle

Skiffle was much nearer to a pop movement proper than either revivalist or modern jazz, and although shorter lived than Rock 'n' Roll, it not only predated it by several months, but its leading light, Lonnie Donegan, was for a long time as popular if not more popular than [Tommy] Steele himself.

Like many of the later pop movements, skiffle too was at first unaware of its potential commercial possibilities. Originally the word had been used, during the 20s, to describe a sort of jazz in which some or all the legitimate instruments were replaced by kazoos, washboards or broom-handle bass-fiddles. Later there was, in British skiffle, a resurrection of the music within the traditional meaning of the term, but at first the word was deliberately misapplied to mean a folk-spot within the context of an evening of New Orleans jazz.

Ken Colyer, the traditional band-leader, was the first to institute the 'Skiffle Session' in this sense. Apprehensive that even his loyal public might find a whole evening of ensemble jazz a little hard to take, he broke it up by allowing his banjo player Lonnie Donegan to change over to guitar and sing a few folk-blues drawn mostly from the repertoire of the American Negro folk-hero Huddie 'Leadbelly' Ledbetter. These sessions were so popular that when Chris Barber left Colyer to set up on his own, taking. Donegan with him, he kept them in as part of the act.

'Rock Island Line' was originally issued as one of the tracks on a Barber LP but was requested so often on radio programmes that it was eventually reissued as a single and, by May 1956, was Number 1 in the charts. Donegan received only the Musicians' Union fee for 'Rock Island Line' but its success persuaded him to leave Barber and go single. Skiffle broke away at this point from its anchorage in traditional jazz and set sail on its own. Within a few months it was a national craze. All over the country skiffle groups sprang up, and several performers of varying merit followed Donegan into the big time. The first British near-pop movement was under way. Not British in its source (which was almost entirely American Negro folk music), but as a movement for which there was, at the time, no precedent in the States. Donegan was indeed the first British artist who managed to sell musical coals to a trans-Atlantic Newcastle; by 28 April 'Rock Island Line' was Number 6 in the American charts.

Yet for all its success it must be remembered that skiffle tended to appeal to a relatively restricted audience. It had nothing to say to the Teddy Boys. It in no way touched those who were looking for a music rooted in either sex or violence. It seemed, from the off, a bit folksy and tended to attract gentle creatures of vaguely left-wing affiliations. It appealed immediately to very young children, a quality which, in other pop movements, took a certain time. Like revivalist jazz then, although being a vocal music it took less application to appreciate, it was in no way an anti-social movement. There were no skiffle riots.

Why did skiffle have such an impact? There was the 'Anyone can do it' side to it; a few chords on a guitar and you were away. There was the charm of the material but, largely, I believe, it was Donegan himself who was responsible. More difficult is to find a reason. His voice was tinny and harsh, his delivery monotonous, his personality rather prickly. True, he knew how to generate a certain excitement, largely through speeding up his tempos, but this alone is hardly enough to explain his success. The answer I suppose is that he personified, during the years of his success, a certain mood among young people, mostly lower-middle rather than working-class young people, and projected that mood for them. The world he sang of was, in its original, a violent world. Leadbelly, for example, was in prison twice on murder charges and had a near psychopathic personality. But Donegan's version was, like the traditional jazz it sprang from, safely distanced from that world. Its violence and harshness were make-believe, and in retrospect he sounds more like George Formby than Huddie Ledbetter. Indeed, as skiffle faded, it seemed perfectly natural that he should desert the American South as a source of material and record old music-hall numbers like 'My Old Man's a Dustman' or 'Does your Chewing Gum Lose its Flavour on the Bedpost Overnight?'

The Trad Boom

Just as a giraffe's neck or anteater's tongue give a clearer idea of the evolutionary process than less exaggerated examples of Darwinian natural selection, so the unlikeliness of the trad boom, its untypical features, are particularly useful in demonstrating certain aspects of pop. For the trad boom was both unexpected and untypical; its heroes were far older than the norm and had been around much longer; the emphasis was instrumental rather than vocal; the sexual aspect was almost non-existent. Yet in the way in which it was sold, over-exposed and abandoned, trad presents a classic case and, in the way in which it contained the seeds of a later movement - British Rhythm and Blues - it demonstrated how, below pop music, lies a common substratum from which the apparently unconnected peaks rear up.

Without Chris Barber it is doubtful if the British trad boom could have taken place; he was the great popularizer, the Sir Kenneth Clark of the traditional idiom. It's true that Ken Colyer's convinced disciples had little time for him. From their viewpoint he had betrayed not only the music, but its message, for Ken had equated traditional jazz with left-wing protest and it was to the sound of a New Orleans marching band that the Ban-the-Bomb columns kept their spirits up on the road from Aldermaston.

During the middle and later 50s Barber had been engaged in polishing away the rough sound of New Orleans traditional jazz, the form of music which had largely replaced the revivalism of the first half of the decade. His didactic, somewhat pedantic presentation flattered a growing audience; he spawned imitators in almost every major town in the country, and it was they who filled the mushrooming jazz clubs and played host to an increasing number of pro and semi-pro London-based bands. Yet off his own bat, I don't think that Barber would have led to a trad boom on the scale it took. He ploughed and fertilized the ground and harvested much of the temporary advantage; he suffered too from its decline; but he lacked both the panache and the common touch needed to transform what was still a committed minority interest into a nation-wide fad. The man who achieved that was the flamboyant Mr Acker Bilk.

Superficially Acker may seem to have been a totally manufactured phenomenon; a golem put together by a Frankensteinian publicist called Peter Leslie. It was Leslie who, faced with promoting a rather rough if dedicated band in the Colyer spirit, imposed the obligatory 'Mr' on all billings, dressed the product in a striped Edwardian waistcoat and bowler hat, and couched its publicity in elephantine pastiche of Victorian advertising prose, larded with unbearable puns. To this already confused picture, he in no way discouraged Acker from projecting and indeed exaggerating his own West Country origins. In effect then the public was asked to accept a cider-drinking, belching, West Country contemporary dressed as an Edwardian music hall lion comique, and playing the music of an oppressed racial minority as it had evolved in an American city some fifty years before. More surprisingly they did accept it. Acker was soon a national idol.

He was of course more than the sum of these unlikely appendages, he possessed the necessary charisma, a great deal of warmth and the ability to produce a simple recognizable sound; but what remains interesting is to try and decide just what this middle-aged clarinettist stood for in the minds of the British public at the beginning of the 60s. My own feeling is that he may have represented some kind of chauvinistic revolt against American domination; that the mixture of Edwardian working-class dandy and rural bucolic came to stand for a pre-atomic innocence when we were on top. Although Bilk himself was carefully represented as apolitical, it was his bowler which the less thoughtful and more emotional fringe of the C.N.D. movement adopted as their symbol, and it was the simple music he purveyed which drew them together at such tribal rites as the later Beaulieu Festivals to rave and riot. Yet simultaneously, for the middle-aged he seemed a reassuring figure, and for the very young, a jolly uncle. From the many-layered amalgam built up by Peter Leslie all could draw what they needed.

In Bilk's wake others prospered. A few went so far as to imitate his stake in fancy dress, but most were content to aim at reproducing the trad sound, an increasingly dispirited formula, which finished up by boring everybody including its exponents. Much of this over-exposure must be laid at the feet of the BBC. It was they, more than anyone else, who were responsible for over-plugging the trad sound so that, not only was a trad band obligatory on such general pop-melanges as Saturday Club, but Jazz Club itself, until that time a serious programme covering the entire spectrum of the music, was ordered to limit itself exclusively to trad.

The reasons for this imposed monopoly are obscure. Was it the unworrying simplicity, the nostalgic archaism of the music, which reassured those in authority? Was it the social ease of the practitioners; for the young lions of the other pop movements tended to treat even beneficent authority with marked disdain? It's difficult to reach a conclusion but what remains certain is that, even for those to whom the revival of early jazz had been a sacred cause for over a decade, the grinding out of the same old tunes in the same old way soon became a monumental drag.

It's worth emphasizing perhaps that, even at the height of the trad boom, the records which made the charts lay for the most part outside the idiom. The first success, Barber's 'Petite Fleur' (April 1959) was a sentimental composition of Sidney Bechet's cloyingly interpreted by Barber's clarinettist, Monty Sunshine; Bilk's greatest hit was the syrupy 'Stranger on the Shore', originally the theme for a children's TV serial; while Kenny Ball, although his chart-busters were superficially 'hotter' in style, chose to record such non-jazz material as 'Midnight In Moscow' or 'The March of the Siamese Children' in a manner which the hard-core jazz fans were to christen 'traddy-pop'. Despite the LPs, which were usually less commercial and aimed at retaining the loyalty of those who had made the whole boom possible, this mixture of compromise and monotony was eventually bound to alienate even the most dedicated trad fans and with no confidence at the centre the whole thing slumped.

There are two other points to raise. Firstly that, while 'the trad sound' was the heart of the boom, many non-trad bands were responsible for the wide public it drew on. In particular the Temperance Seven are important here: Skilful and solemn, they exploited a weakness for nostalgic camp by reconstructing the banal charm of the white dance music of the 20s and early 30s within an Edwardian visual framework. In this they represented a constant thread in pop music; the yearning for a simpler earlier time masked by irony; the musical equivalent of the rash of Union Jacks with which 'Swinging London' was to conceal its uncertainty.

The other point worth stressing is that within trad itself and at the height of the boom there were many who rebelled against its increasing conformity, notably Chris Barber himself. Chris moved away from the sound for which he was largely responsible long before it reached its height. His wife, Ottilie Patterson, who during the early 50s had sung in a comparatively convincing approximation to the style of Bessie Smith, took to plugging both Gospel music and urban Rhythm and Blues. Barber was also responsible for introducing many of the originators of both these idioms to the British public and indeed of encouraging the embryonic talents of the emerging British R and B movements. Yet when the slump came his name was too much associated with trad to allow him a free pardon, and the only band-leaders to emerge comparatively unscathed were those who had most resolutely refused to cash in: that is, on the one hand, Ken Colyer, the great incorruptible of New Orleans jazz, and on the other Alex Welsh whose dixieland-flavoured band had never totally convinced the diehard traddies, and who in consequence lay outside the direct path of the backlash.

Back to the Miscellaneous page